While there were a variety of winners at the Academy Awards last Sunday, few seemed to emerge as dominant as Sean Baker’s “Anora,” a crime drama about a woman partaking in a relationship with the son of a Russian oligarch. While the stereotype of “Oscar-bait” is legendary when it comes to Hollywood awards season, “Anora” seems at odds with that stereotype, being set in contemporary times, lacking the backing of a major studio and covering a topic that Hollywood normally is uncomfortable with.

At the same time, “Anora” may not be as radical as it sounds on paper. Considering how the film industry seems dominated by multimedia franchises run by effectively one multi-billion dollar company, a film so decidedly auteurist as “Anora” seems like a return to the often salivated over days of New Hollywood: the period in the 1960s and 1970s where individual filmmakers captained undisputed control over big-budget studio funded ventures. And ironically, Mikey Madison, the star of “Anora” who plays the titular character, seems to represent the conventional fleeting beauty that Hollywood is obsessed with. This seems especially ironic considering a sticking point of Best Actress runner-up Demi Moore’s film “The Substance,” a film in which the shallow materialism of Hollywood served as the primary theme.

Ultimately, the Academy voters who decide the winners of these awards are conservative people; while they cannot deny forces of innovation on one hand, they fundamentally prefer safe, prestigious films that don’t rock the boat too hard. This is not a new revelation, of course; Oscars history is filled with unpopular upsets, like “The King’s Speech” beating out “The Social Network” for Best Picture in 2010, or “Crash” landing its infamous upset over “Brokeback Mountain” in 2005, or even “Roma” getting beat out for Best Picture by “Green Book,” a film which no one under the age of 60 seems to like. If we look past Best Picture, it gets more egregious when Jamie Lee Curtis’ Best Supporting Actress win in 2022 is taken into account.

Still, the Oscars are made up of humans, who are aware of the criticism they regularly receive. After Will Smith’s slap at the 94th Academy Awards in 2022 and subsequent winning of Best Actor without facing any substantive consequences, the Academy made a sharp turn toward a more popular pick the following year, granting a sweep to “Everything Everywhere All At Once,” an A24 sci-fi action comedy directed by Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert that primarily built hype through online film meme culture. “Everything Everywhere All At Once” was effectively the exact opposite of Oscar-bait, primarily appealing to millennials and younger, and combined with Brendan Fraser winning Best Actor after a much hyped online comeback campaign for a “Brenaissance,” it seemed like the Oscars were now playing for the people rather than the industry.

Now, of course, this proved temporary; the following year, the more typically Oscar-bait “Oppenheimer” swept, though the Academy lucked out with the “Barbenheimer” meme making “Oppenheimer” into more of a populist pick for Best Picture.

Much like “Anora,” “Oppenheimer” was helmed by a distinctive auteur, in that case Christopher Nolan, which consistently appeals to the memory of New Hollywood that the Academy voters cherish. This seems to set the stage for what the Oscar voters desire these days: films with a strong, director-driven vision that still keep with Hollywood’s more archaic elements.

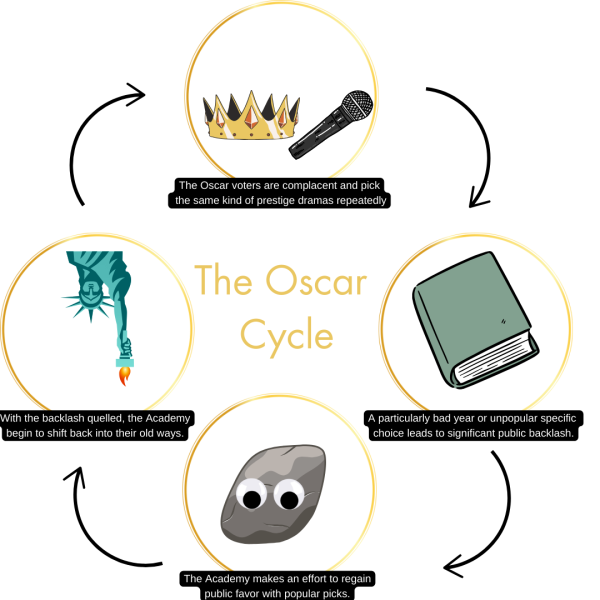

There’s a fairly simple explanation for why the Academy votes this way: the Oscar cycle. This entails an initial period of comfort for the Oscars, in which conventional prestige pictures win repeatedly, which drives audience dissatisfaction with the Awards that inevitably culminates in a year with an especially large blowback. In response, the Academy awards a more popular pick the following year, to which they win back audience attention and respect, before settling back into their old ways in the years after that. While this is not necessarily a bad thing, it leads to a Best Picture having to have a certain respectability, in a way; it will take a very different institution for an animated or “genre” film to win Best Picture. “Anora” serves as the latest representation of this: how could a subversive film like “The Substance” have its leading lady win Best Actress, when it shows itself to be critical of Hollywood?

Now, the Academy obviously is not incapable of change; period films, once often joked about as being built for winning Oscars, now seem out of fashion for Academy voters presently. Still, there is a reason why “Anora” beat out its more bold opposition and why establishment favorite Adrien Brody pulled out the Best Actor win against his more intrepid opposition. They ultimately reaffirm that the Oscars are allowed to stay the way they are, and while the Academy may one day grow to be better at reflecting the will of the masses, it remains firmly entrenched in the industry for the time being.