From Scouting to Signing Day: Behind the Student-Athlete Recruitment Process

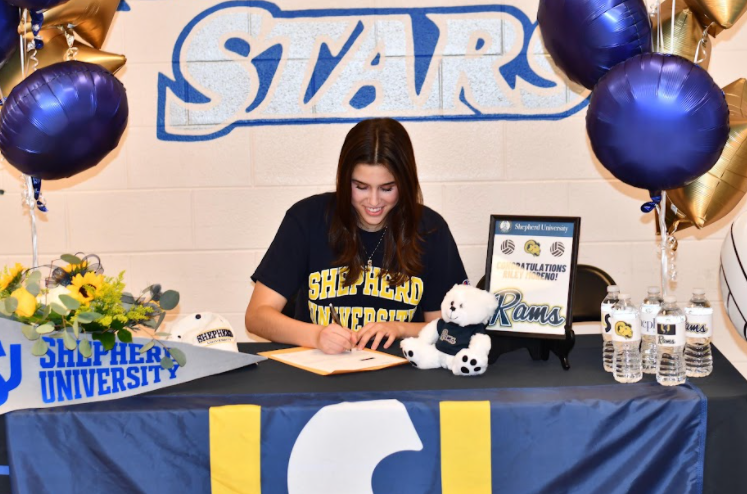

Moreno signing her National Letter of Intent for Shepherd University to play volleyball

February 4, 2022

The process for student-athletes getting recruited to colleges is unlike the path taken by most students. From scouting to contacting coaches, student-athletes take an unconventional route to make their final decision.

Athletes typically initiate the process around freshman or sophomore year, though some start as early as middle school.

“There’s tons of schools and universities out there. I think it’s just harder when you start your junior year and your senior year, and sometimes you kind of let some of those opportunities slip up,” said Todd Weimer, boys volleyball coach.

Athletes start by developing their profile, collecting films and highlight videos to show to coaches and post online.

“[My mom] would spend hours and hours breaking down film of my game, putting it together, making it so I can upload it to my profile and send it to coaches,” said Riley Moreno, senior committed to Shepherd University to play volleyball.

During early high school, college coaches attend tournaments and games to scout talent and look for students showing promise. However, what they look for goes beyond stats.

“They’re listening to how you’re talking to your teammates and your parents after the games. It’s awesome that you can perform on the field, but the things you do off the field have to be just as important, too,” said Jayden Lobliner, senior committed to Kansas State University to play baseball. Coaches use scouting as an opportunity to look at attitude and sportsmanship.

Athletes themselves also play a very large role in communication. Students are encouraged to reach out to many coaches very early, as soon as high school starts.

“I think it’s really important just to be communicating back and forth, whether it’s email, or whether it’s in writing or you know, even text messages or social media,” said Weimer.

The recruitment process is regulated by national college athletics organizations, such as the NCAA. These organizations have strict calendars regarding coach contact, evaluation and offers. It can be different for every sport and year, so athletes must be well-informed about their specific sport.

One of these schedule regulations is the dead period, a time in which students and coaches aren’t allowed to contact each other for a certain period of time.

“The dead period basically means coaches cannot talk to recruits. They’re off-limits. And so it’s really just to level out the playing field,” said Weimer. While athletes may maintain online communication, talking to coaches face-to-face, or receiving offers, isn’t allowed.

“Because of COVID-19, our graduating class got delayed. So the day where we were able to speak to schools kept getting pushed back and back,” said Moreno.

Once this period is up, students and coaches can meet, and conversations become more serious as offers start coming into play.

“What kind of major? What kind of career am I looking at? Do I want to go to a big school or a small school? Geographic location? Those are some key decisions [student-athletes] probably need to start thinking about,” said Weimer.

One of the biggest challenges for student-athletes is striking the right balance between athletics and academics.

“I’m going to have to manage my time really well in college. You’ll have baseball practice, training, you gotta eat right, you have to get to class. It’s gonna be a lot,” said Lobliner.

As a result, athletes need to make a decision when it comes to the athletic division they will be competing in, with some being more rigorous than others.

“Having a high-level school at a lower division, but that has everything that I want academically was just so much more important than playing 30-hour weeks at a big school and really struggling academically,” said Moreno.

Communication with coaches is also an important factor, as they will be the ones students work with a lot in college.

“It was phenomenal with the talks that I got to have with them,” said Lobliner. “[The biggest factor] ended up being, for me, the coaching staff.”

Once students make their decision, they can make a verbal commitment saying they are committed to a college, though the official contract has not yet been signed.

“You have this National Letter of Intent, [athletes] sign it, and then send it in, and that makes it concrete,” said Weimer.

This is done on Signing Day. Done throughout the year, the specific time and date is unique to each athlete. At their high school, athletes will bring in coaches, family and friends to celebrate and sign the National Letter of Intent.

“There were lots of videos I had to watch, explanations and many contracts just beyond the Letter of Intent. The actual signing and the balloons and all the excitement wasn’t as nerve-wracking as I anticipated,” said Moreno.

Athletes then start preparing for their college season, through talking to coaches, beginning conditioning or finishing up their high school season.

“What they have me doing is looking into some college summer leagues, playing against college guys, getting that high-level experience throughout the summer and eventually just joining them into the fall,” said Lobliner.

Coaches and students alike encourage new athletes to be dedicated and bold, saying that if they have the goal of playing in college, students should push for it.

“Be persistent. You know, dreams happen. But in order to make dreams work, you have to put the time and effort to make it work,” said Weimer.